The Truth About Fluoride

Toxic by Nature, Trusted by Habit

We often inherit our health beliefs the same way we inherit family traditions. They’re passed down, repeated often, and eventually accepted as facts.

Fluoride is a perfect example.

For decades, we’ve been told it protects our teeth, belongs in our drinking water, and stands as a hallmark of modern public health. But just because something is familiar doesn’t mean it’s true. To understand fluoride clearly, we need to go back to the basics:

What exactly is fluoride?

Where does it come from?

And how did it end up in our water and toothpaste?

Once we look at that foundation, the story of fluoride looks very different from the one we’ve been given.

Contents

What Exactly is Fluoride?

How Fluoride Entered Public Health

Fluorosilicic Acid - From Waste to Tap Water

Sodium Fluoride - From Poison to Toothpaste

Do Humans Actually Need Fluoride?

A Common Counterargument

Critical Reflections

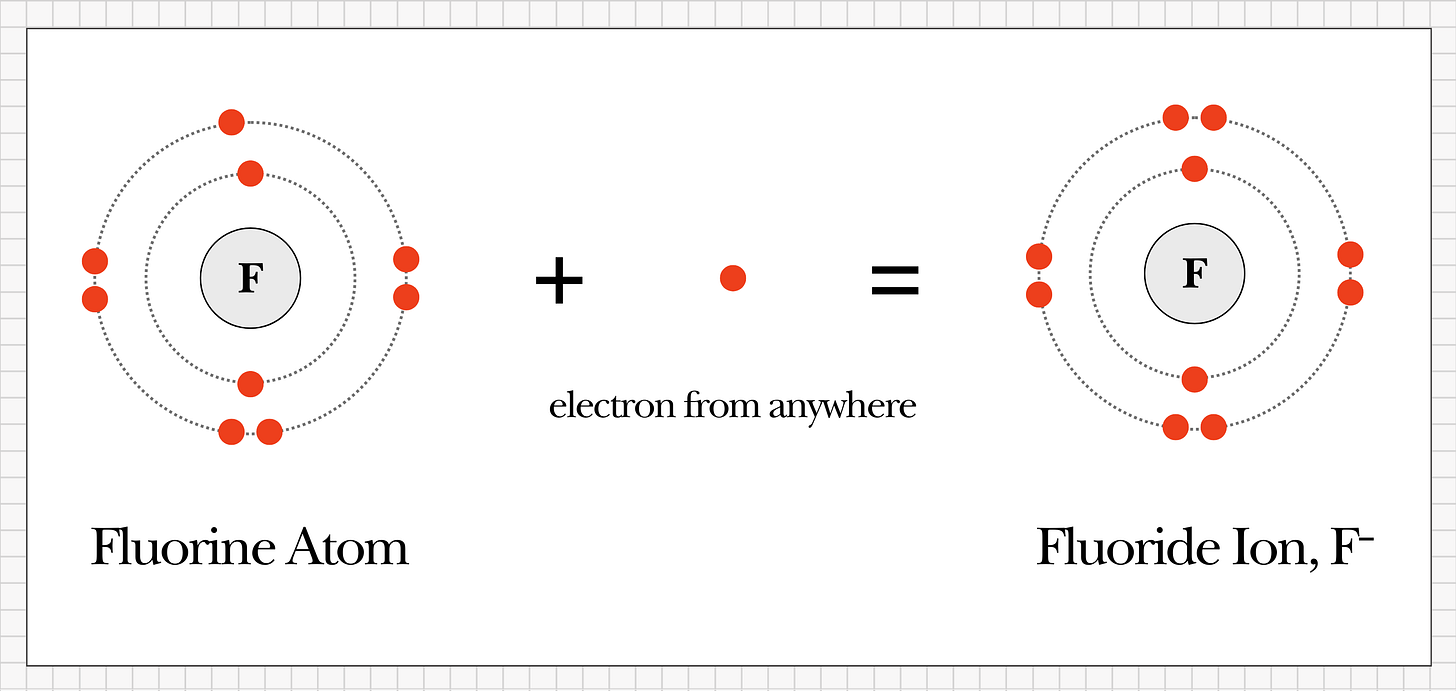

Fluorine vs. Fluoride

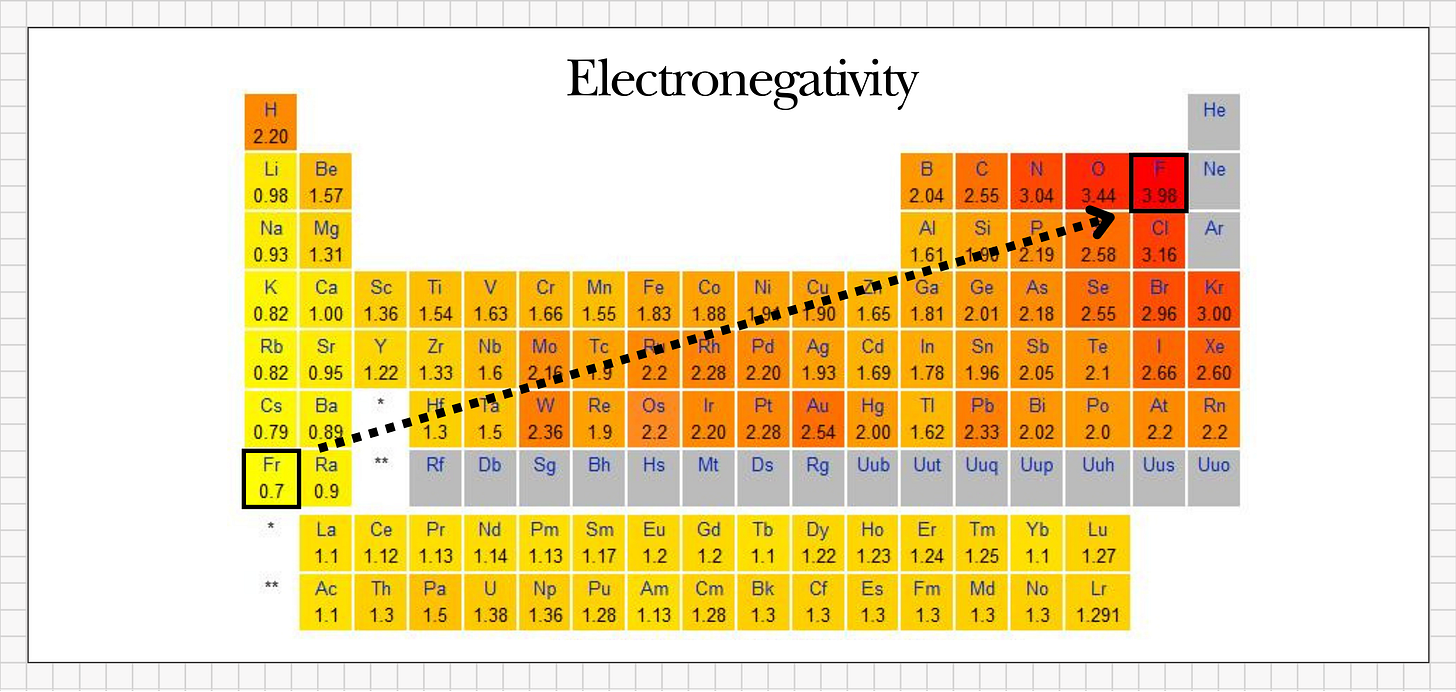

To understand fluoride, we first need to start with fluorine.

Fluorine is a natural element on the periodic table, and it’s unique because it’s the most reactive element known to science. Because it’s so reactive, fluorine is never found on its own in nature - it simply can’t exist that way. The moment it appears, it instantly bonds to whatever’s nearby.

Think of it like a magnet that can’t sit still.

When fluorine bonds with something else, it becomes a fluoride compound. The word “fluoride” simply means fluorine is present as part of a chemical pairing.

For example, when fluorine bonds with calcium, it creates calcium fluoride.

▶︎ Key Point: Fluoride never exists alone. It always appears as part of a compound.

Natural vs. Man-Made Fluoride

Health agencies, websites, and public figures often describe fluoride as a “naturally occurring substance” found in soil, water, rocks, and even animals. While this statement is technically true, it can be misleading. It gives the impression that fluoride must be safe and beneficial simply because it exists in nature.

But this view overlooks two key facts:

Natural does not always mean safe.

Fluorine may be a naturally occurring element, but that doesn’t make it healthy for the human body. Arsenic, lead, aluminum and mercury are also naturally occurring elements, yet they’re all unquestionably toxic.The fluoride in water and toothpaste isn’t natural.

The fluoride added to tap water and toothpaste isn’t elemental fluorine or naturally occurring minerals. They’re man-made chemicals produced in factories or recovered as industrial byproducts. These forms of fluoride do not occur in nature.

▶︎ Key Point: The fluoride in tap water and toothpaste comes from industry, not from nature. And the word “natural” should never be confused with “safe.”

In the United States, fluoride was first added to public water supplies in the 1940s, followed by its introduction into dental products in the 1950s. This process is accomplished by adding one of three chemicals:

Fluorosilicic acid (H₂SiF₆)

Sodium fluoride (NaF)

Sodium fluorosilicate (Na₂SiF₆)

Our focus will be on the first two, since they represent the main sources of everyday fluoride exposure.

The main chemical used to fluoridate public water is fluorosilicic acid. Despite its role in public health today, its origins have nothing to do with health or medicine - its story begins in heavy industry.

In the early 1900s, fertilizer factories released huge amounts of fluoride gases into the air, mainly hydrogen fluoride (HF) and silicon tetrafluoride (SiF₄).

These gases poisoned nearby farmland, burning crops and crippling livestock. Cows developed a severe bone disease (skeletal fluorosis), lost their teeth, and many died.

By the 1950s, fluoride pollution had caused more lawsuits from farmers than any other industrial contaminant of that era.

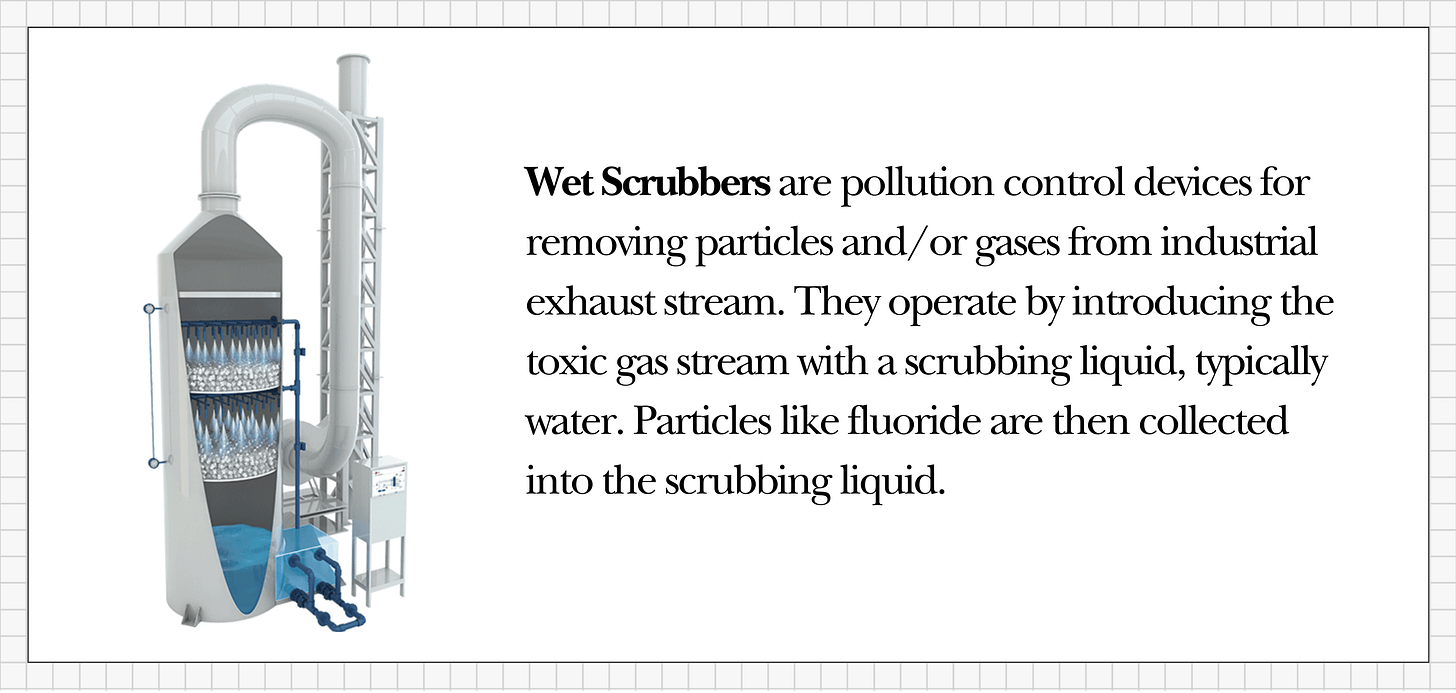

To stop the lawsuits and environmental damage, industries installed devices called wet scrubbers. These machines sprayed water to trap the toxic gases before they escaped into the air.

This reduced air pollution, but it created a new problem: the gases dissolved into the water formed a highly corrosive liquid called fluorosilicic acid.

Now companies had thousands of gallons of hazardous waste on their hands - difficult and expensive to dispose of safely.

Rather than throw it away, fertilizer companies found a buyer: local water utilities. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, truckloads of fluorosilicic acid were being drip-fed into public drinking water as the new “cavity-prevention” additive.

In effect, the same fluoride waste that once killed cattle and destroyed farmland was now rebranded as dental care.

The second major fluoride compound we encounter is sodium fluoride. Today, it’s most famous as the active ingredient in toothpaste.

Sodium fluoride is not a naturally occurring mineral; it’s produced through industrial chemical processes, often as a byproduct of manufacturing other materials.

For over half a century, every major use of sodium fluoride has revolved around its ability to kill or corrode.

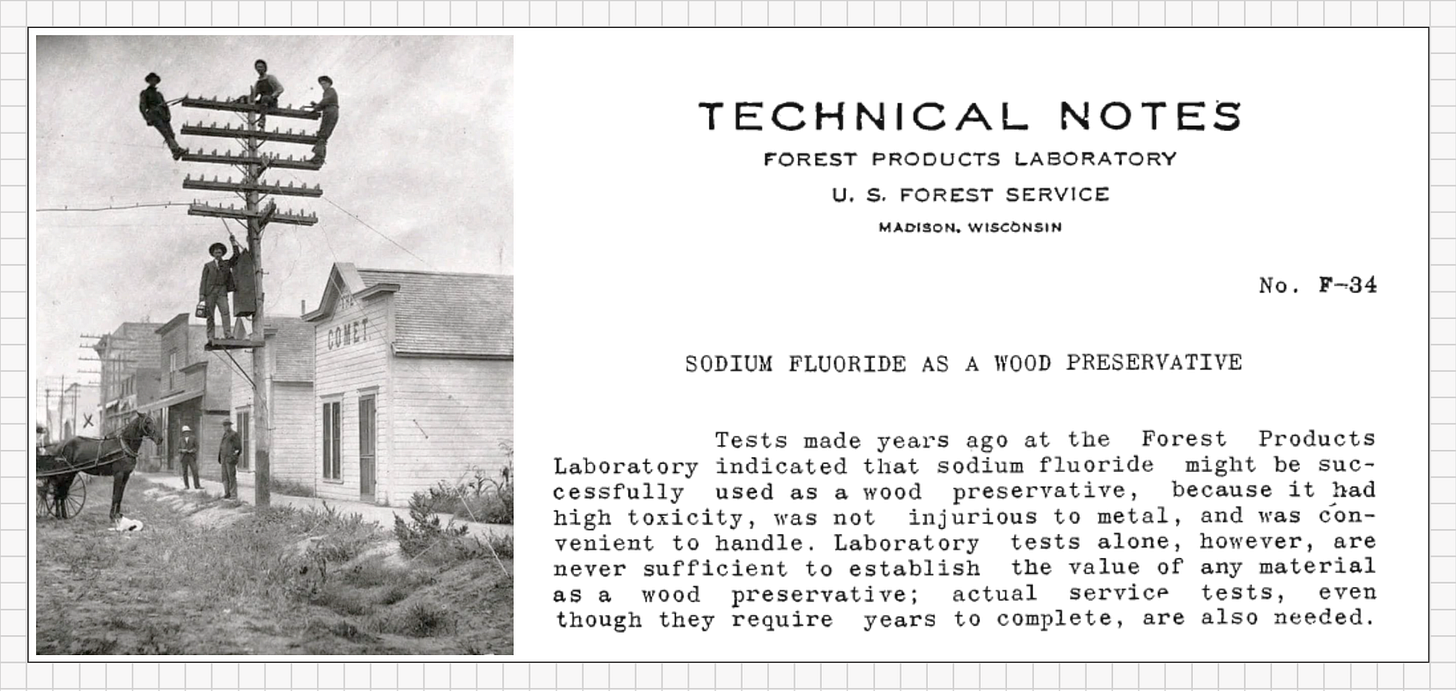

Late 1800s – Wood Preservative

Railroads and telephone companies faced a costly problem: wooden ties and poles rotted quickly outdoors. Rain, fungi, and insects ate through the wood, cutting short its lifespan. The solution wasn’t paint or varnish… it was poison. Workers soaked the lumber in sodium fluoride, relying on its toxicity to kill fungi and insects before they could destroy the wood.

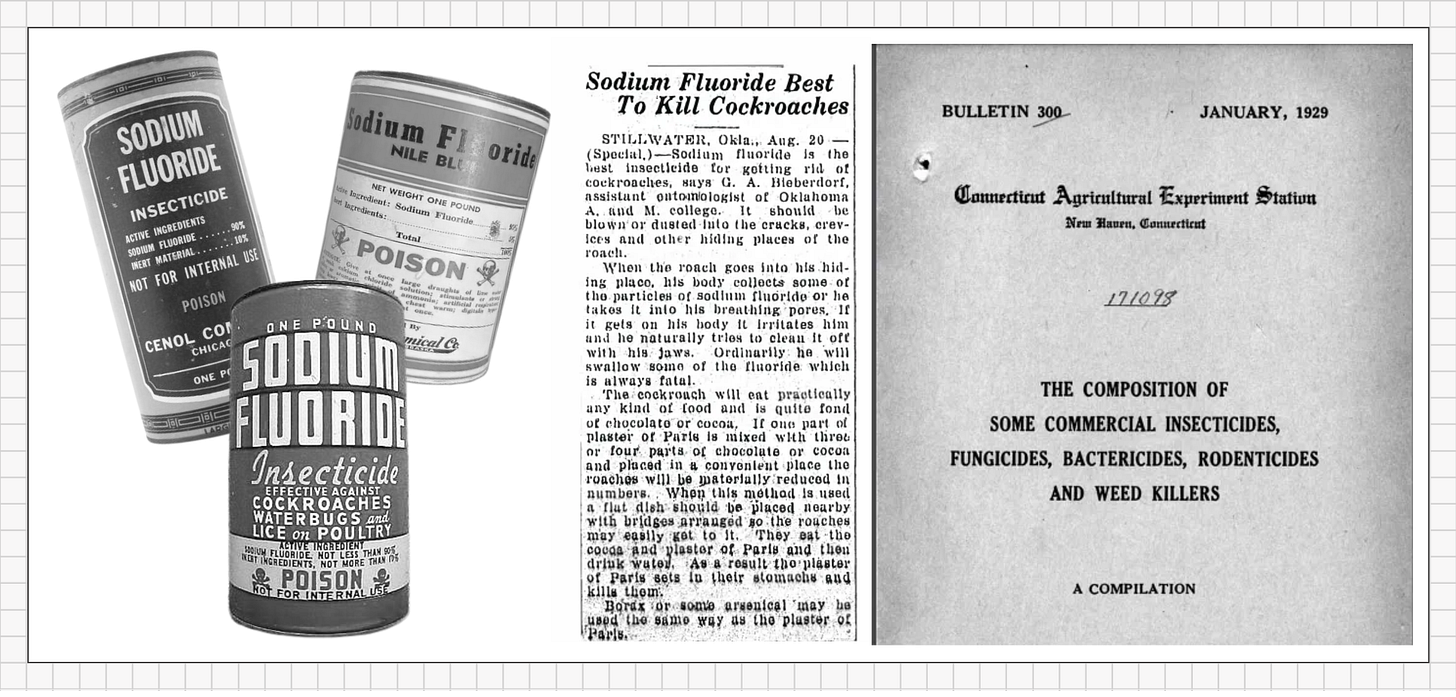

Early 1900s – Pesticide & Rat Poison

Food supplies and homes were under constant threat. Rats destroyed grain and spread disease, while roaches and lice infested barns and kitchens. To fight back, sodium fluoride was packaged in small tins and sold in stores. Farmers scattered it in barns to kill rodents, and city dwellers sprinkled it in kitchens to drive out insects.

1920s-1930s - Heavy Machinery

The steel and aluminum boom created new problems. Molten metal carried impurities that weakened it, and machinery rusted quickly under harsh conditions. Sodium fluoride became the fix. Mixed into molten metal, it pulled impurities to the surface where they could be removed. Applied to machinery, it ate through rust and grime, leaving the surface clean.

For more than fifty years, sodium fluoride was prized for one defining trait: its toxicity. It preserved wood, killed pests, and cleaned heavy machinery. Never once was it considered a nutrient, a medicine, or anything remotely related to health.

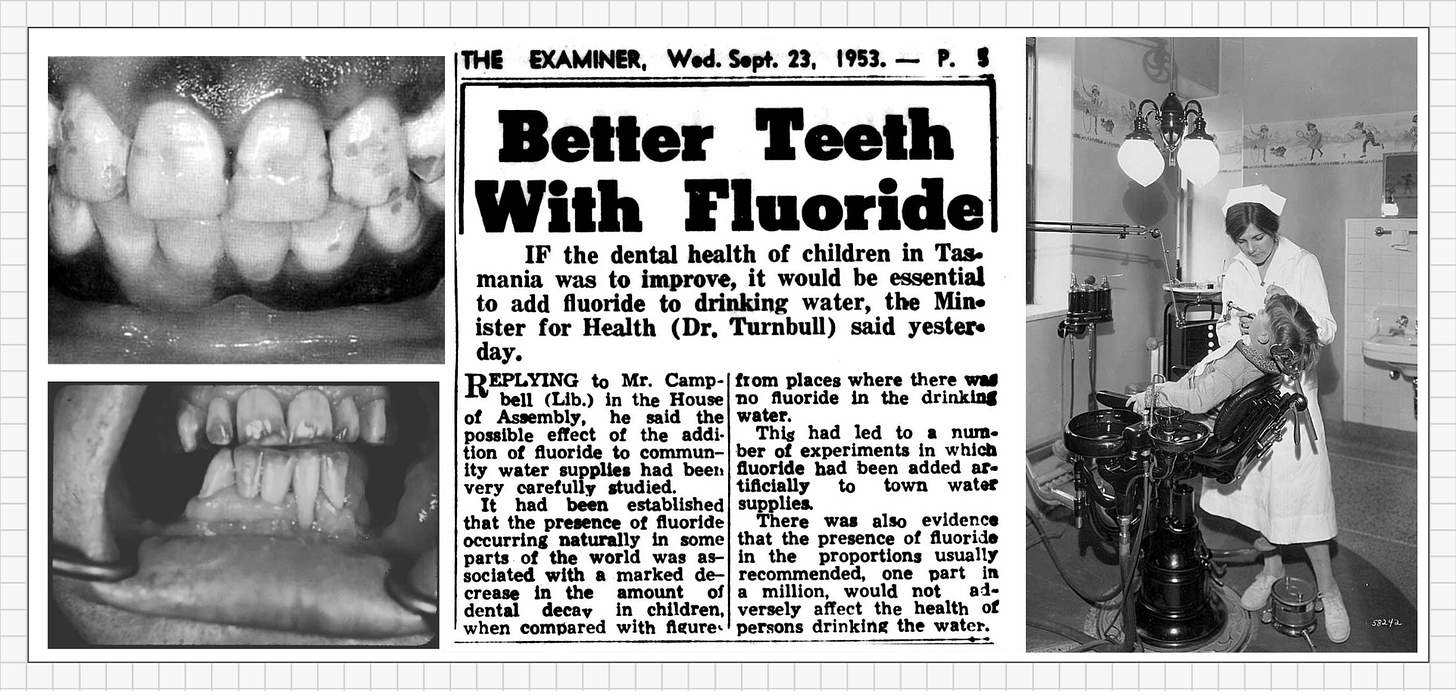

That story began to shift in the 1930s and 1940s. Researchers noticed that children living in areas with naturally high levels of calcium fluoride in their water appeared to have fewer cavities... though their teeth were often stained, brittle, and weak - a condition later named dental fluorosis.

This observation sparked a new idea: perhaps fluoride could help prevent tooth decay. But instead of using natural calcium fluoride, scientists turned to sodium fluoride: it was cheap, water-soluble, and already being mass-produced by chemical companies.

By the mid-20th century, the transformation was complete:

1940 ⇢ Researchers began applying sodium fluoride solutions onto schoolchildren’s teeth in test communities.

1945 ⇢ Grand Rapids, Michigan became the first city to add sodium fluoride directly to its water supply.

1955 ⇢ Crest launched the first fluoride toothpaste, proudly listing sodium fluoride as the “active ingredient.”

Within a single decade, the very same compound once packaged and sold as “rat poison” was rebranded as a health product - brushed into the mouths of millions of children and celebrated as progress in modern dentistry.

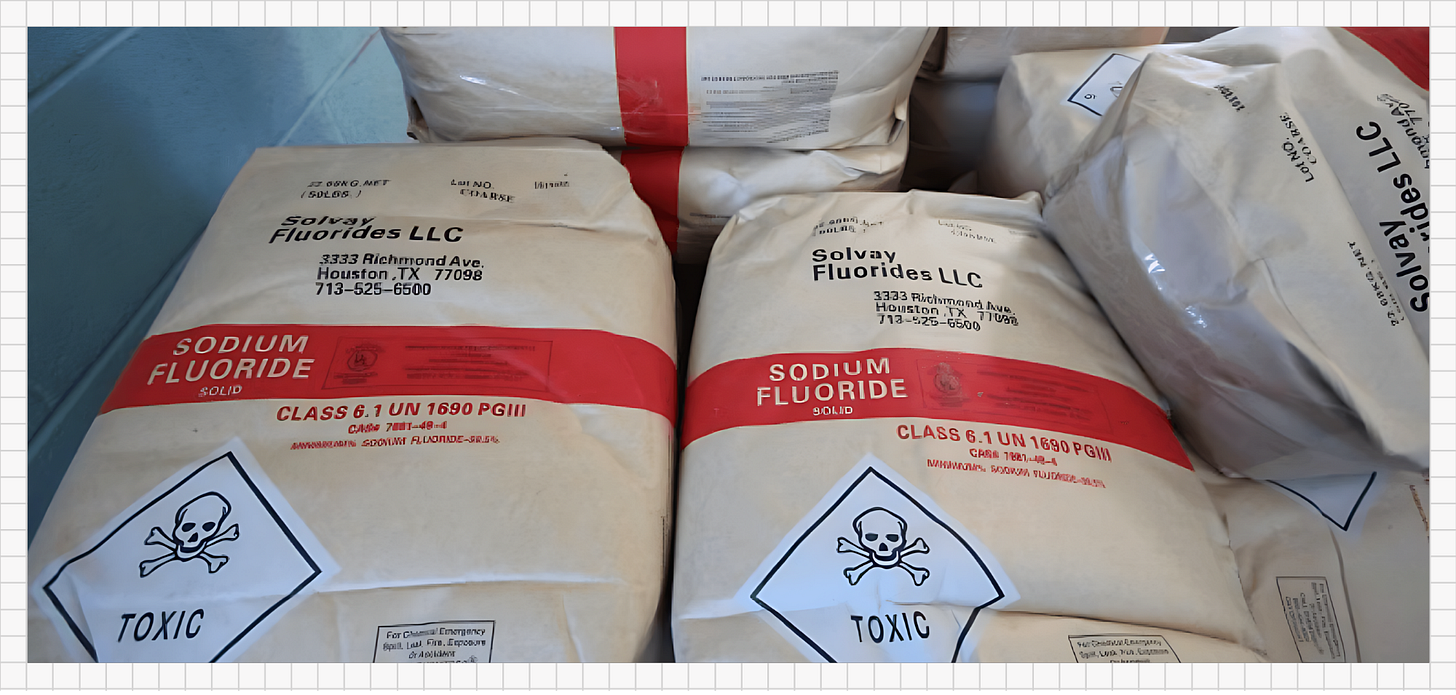

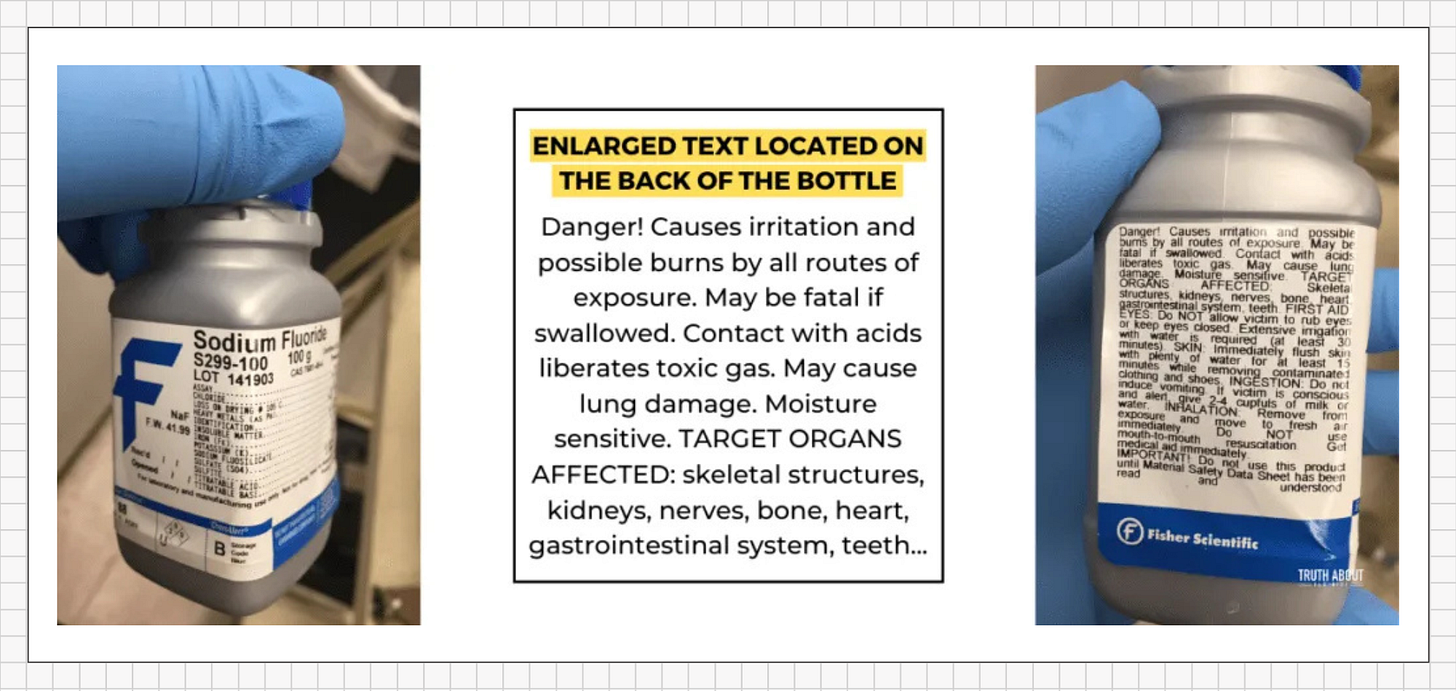

Note to readers: The claim that calcium fluoride reduced cavities never withstood serious scrutiny. It relied on flawed studies, most notably data cherry-picking and selection bias, and has long been discredited.Despite its new image, sodium fluoride’s identity as a toxic chemical hasn’t disappeared. Even now, it is legally classified as an acutely toxic substance. Industrial-grade containers carry a skull-and-crossbones hazard label to warn anyone who comes near it.

In facilities where it’s stored or used, workers never handle it casually:

⚠️ Protective clothing is required. Lab coats, coveralls, nitrile gloves, goggles, and face shields are mandatory. Ventilation systems run constantly, because inhaling even a trace of sodium fluoride dust can damage the lungs.

⚠️ Contact is dangerous. A splash on the skin can cause chemical burns; in the eyes, it requires emergency flushing and medical treatment. Ingestion is worse: just a few grams - about the weight of a sugar packet - can be fatal to an adult.

⚠️ Even storage and disposal are tightly controlled. Sodium fluoride must be kept under lock and key, with detailed hazard logs. Any spills or waste must be treated through approved hazardous-materials facilities.

These protocols aren’t excessive - they are required by law. They exist because sodium fluoride is still recognized for what it has always been: a highly toxic industrial chemical.

For much of the mid-20th century, fluoride was promoted almost as if it were an essential nutrient - something our bodies need for strong teeth, much like calcium for bones or vitamin D for healthy growth.

In the 1950s, some public health officials even spoke of a supposed “fluoride deficiency,” suggesting that cavities were the result of too little fluoride in the diet. This idea quickly took root, and fluoride was widely accepted as necessary for health.

But as scientific understanding advanced, this claim unraveled. Decades of research by major health authorities failed to identify any essential biological role for fluoride in the human body:

“Sodium fluoride used for therapeutic effect would be a drug, not a mineral nutrient. Fluoride has not been determined essential to human health.” - FDA 1963

“In summary, FDA does not list fluorine as an essential nutrient.” - FDA 1990

“Fluoride is not an essential nutrient… there was no evidence that we require it for growth, development, or any normal metabolic process.” - U.S. National Research Council (NRC) 1989 & 1993

By the early 2000s, even public health agencies had backed away from describing fluoride as “nutritional”:

“The amount of fluoride stored in tooth enamel is not what determines cavity risk.” - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2001

“Fluoride is not a nutrient and is not required for any biological function in the body.” - World Health Organization (WHO)

The defense of fluoride almost always rests on one claim: it’s dangerous at high levels, but safe in small amounts. This “dose makes the poison” argument has been repeated for decades to justify its place in toothpaste and drinking water.

But it overlooks two critical truths:

Fluoride is not essential to the body. As mentioned above, health authorities themselves admit this. It is not a vitamin, not a mineral, and not a nutrient in any sense. There is no such thing as “fluoride deficiency.” No disease, not even cavities, comes from not having enough fluoride. Strong teeth and good health are fully possible without ever ingesting it.

Lowering the dose doesn’t eliminate the risk. A chemical that corrodes, poisons, and kills at high levels does not suddenly become harmless at low ones. Toxicity is not a light switch… it exists on a spectrum. Dilution may reduce the danger, but it does not erase it.

Which brings us to the obvious question: If the human body has no biological requirement for fluoride, why take on any risk at all? Why normalize exposing people, and especially children whose bodies are still developing and more vulnerable, to daily doses of an industrial byproduct?

In any other area of health, the idea of giving infants and children trace amounts of a hazardous chemical every single day would be unthinkable. Yet through decades of repetition and reassurance, fluoride has been reframed as “good public health.”

The history of fluoride in public health is not the story of science discovering a biological need. It’s a story of marketing reshaping perception. Fluorosilicic acid, once labeled as a corrosive industrial pollutant, is now poured into tap water. Sodium fluoride, once packaged and sold as rat poison, is now brushed into children’s teeth. The compounds themselves didn’t change. They weren’t purified or transformed into something safer. What changed was the story. Industrial waste was rebranded as prevention.

The truth may feel uncomfortable, but it is also liberating. When we set aside assumptions and look honestly at the evidence, fluoride can be seen for what it is…and what it is not. From there, we can move toward a model of health grounded in truth, nourishment, and respect for the human body.

Practical Steps for Families

Toothpaste: Choose fluoride-free for the entire family. Infants and young children are most at risk because they often swallow toothpaste, but adults are not exempt. Daily, lifelong exposure adds up. Fluoride-free toothpaste, along with proper brushing and a nutrient-dense diet, is enough to maintain healthy teeth.

Water: If your tap water is fluoridated, always filter it before drinking or cooking. A reverse osmosis (RO) system is one of the most effective options, and trusted spring water that’s been verified for low contaminants is another safe option.

Parting Note:

Fluoride is a drug —not a nutrient— and should be regarded that way. Like nitroglycerin for chest pain, it can manage symptoms but never corrects the disease itself. In the rare cases where its use can be justified, it should remain temporary, carefully managed by a dentist, and always part of correcting the true underlying causes.Next in This Series

In our next issues, we’ll go deeper, unpacking what fluoride actually does inside the human body. From its effects on the brain, thyroid, and bones, to the way it interacts with children’s development. Stay tuned!

If this message felt important to you, please share it with your friends and family - especially new parents. The foundation of lifelong health rests on the habits and choices we make each day.

🫶🏻 This!! So informative